By Steven Zeitchik – Contact Reporter

For many people, the JT Leroy scandal of a decade ago was a passing headline, a story that had lasting resonance to a few publishing insiders at best.

But as the indie-film director Jeff Feuerzeig discovered, the Leroy affair was much more than we know — a strange, existential and ultimately thrilling story of a woman donning identities with a degree of spy-novel ambition (and, sometimes, Mel Brooks absurdity).

Feuerzeig is the director of “Author: The JT Leroy Story,” a new documentary about the nearly decade-long invention pulled off by the writer Laura Albert. The movie premiered at the Sundance Film Festival this weekend ahead of playing on A&E and likely in theaters later this year. With vast access to Albert’s copious archives and thoughtful on-camera remembrances, Feuerzeig constructs a tightly woven and almost unbelievable yarn.

“If I didn’t live through making the movie, I don’t know if I would have believed what happened,” Feuerzeig said in an interview at a condo here shortly after the film premiered this weekend.

Albert, the film tells us, was a depressed person struggling with body image and a penchant for calling phone-help lines when she decided to seek out the experimental writers Bruce Benderson and Dennis Cooper in the mid-1990s. Albert had been noodling with some gritty experimental fiction, and soon enough she had accrued some allies and, eventually, a publishing deal.

She also created a rather rich biography. Rather than the 30-ish woman living with her boyfriend in San Francisco she actually was, Albert claimed she was Terminator (later Jeremiah Terminator, later JT, later JT Leroy), a 20-year-old, gender-questioning boy who grew up in truck stops with a prostitute mother, a young man who had struggled with drugs, suffered from HIV and flived 100 lives in just a few years.

Soon her (his) celebrity grew, Leroy’s fiction (and back story) attracting a raft of famous fans–not just in the publishing world but superstar musical acts like U2 and global celebs including Asia Argento.

What follows is the kind of identity-swapping scheme that a Hollywood producer would reject as too fantastic. At first Albert just pretended Leroy was a recluse (in one of several remarkable bits of video, she attended a reading in which other authors read from the work as she sat anonymously in the audience).

Actors and filmmakers visit the L.A. Times photo and video studio at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival. The festival takes place annually in Utah and is one of the largest independent film festivals in the United States.

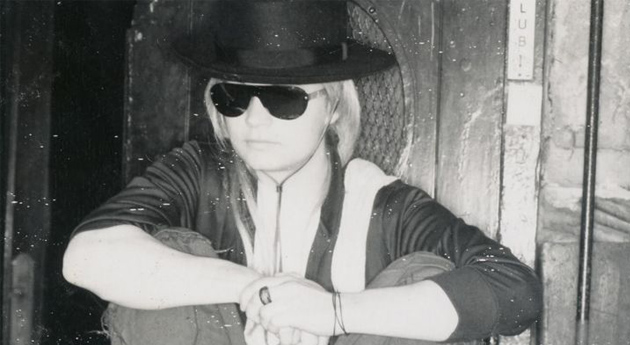

Soon, though, Albert needed more characters to feed the beast. Savannah Knoop, the sister of Albert’s husband, was enlisted to pose as Leroy in public appearances, in sunglasses and colorful headwear.

Sound crazy? It gets wilder. Albert herself started becoming different people too, including “Speedie,” an assistant who was always accompanying Leroy. This was as complicated as it sounded–not only because Albert had to find ways to pull the strings, puppeteer-style, with her sister-in-law when Leroy appeared in public but because she had to keep track of who was saying what to whom. When Savannah met, as Leroy, with Gus van Sant over a planned film adaptation, Albert had to line up that conversation with what she was saying to Van Sant on the phone as Leroy.

This became even more complicated when Savannah, as Leroy, had an affair with Argento.

“My reaction to this story was the same as everyone else’s,” Feuerzeig said. “It’s a great literary hoax, and that was that. But as I started reading all these stories I thought, ‘There’s more here; there’s something we’re not hearing.'”

Albert had never told her story in full before, and might have turned down Feuerzeig if he hadn’t directed “The Devil and Daniel Johnston,” a Sundance standout from a decade ago about another notable but tortured artist, the titular songwriter. That had helped convince her, Fuerzeig said, that he would give her fair hearing and her tale full weight. (Albert also said at the screening that she was won over by the fact that “he was Jewish and he was punk rock,” which, she said, meant he rejected certain societal norms.)

The movie offers some intriguing theories about why Albert, who had an exceedingly difficult childhood, was so prone to creating these personae. (As a teenager she was using other people as “avatars” in the real world, which is as unusual as it sounds.) But it also raises universal questions about identity and selfhood. After all, who hasn’t adjusted or even created guises depending on context? Was Albert fundamentally different from the rest of us, the movie asks, or just more ambitious and public about it?

Albert did mislead a lot of people, and the sight on-screen of publishing stalwarts, like the agent Ira Silverberg, coming to terms with what she had done is pointed and won’t win Albert any sympathy.

But as the director said, it’s also clear the story was not as simple as that of a con man — as seen here, Albert was less a fame-hungry opportunist than a confused person and artist who, in struggling to figure out who she was, fell backward into fame.

“This wasn’t something she was looking for. The books stood on their own. and the fans — including the celebrity fans — came to her,” Feuerzeig said.

Noted Albert at the screening: “My motives were not the motives that were attributed to me.”

(Most of her celebrity relationships, it should be said, were of the superficial sort–with two major exceptions. She formed a close relationship with “Deadwood” creator and resident Hollywood philosopher-poet David Milch, even working on an episode of the HBO show, as well as Smashing Pumpkins frontman Billy Corgan. Long before journalists began uncovering her deceptions, she spilled all her secrets to both of them; they maintained her confidence.)

Whether her books would have been as successful without the Leroy biography is a question the movie leaves open. Certainly it’s fair to think they fueled her success.

But Albert was also, in the end, a fiction writer. Her books, especially bestseller “The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things,” garnered attention because of the quality of its prose. Her biography, mattered, but only partly.

“Author” also implicitly raises the question of whether our demands from fiction writers are unfair and contradictory. On the one hand, we want them to possess the flair for wild imagination that leads to great work, but we want that imagination to stop short in every other realm of life.

The film provides no easy answers, choosing instead to become a more complex exploration on the nature of self and story. “I don’t blame anyone on the receiving end of what Laura was doing,” Feuerzeig said in the interview. “But I don’t want to judge and I don’t want to moralize. I just want to show what this woman did, and what she went through.”

Whatever one’s conclusions, it’s clear that categorizing the Leroy affair as a simple huckster tale is insufficient. “I’m not a hoax, I’m a metaphor,” Albert says in the film to a skeptical reporter. She may be splitting the atom. Or she may be engaging in one more brilliant creation.